The Smallsword: An elegant weapon for a more civilised age

“A man may receive many cuts with a Broadsword, and live after all, but if he recieves one thrust of a smallsword, it may prove fatal”- Archibald Mcgregor 1791

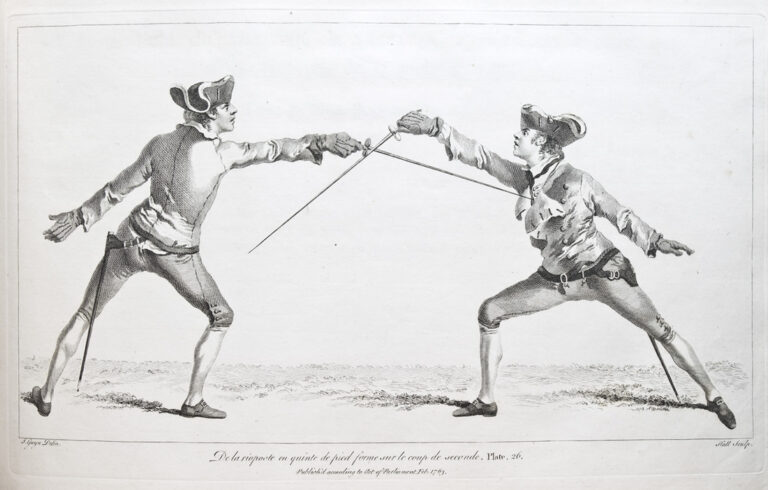

Lightning fast attacks, artful counter-attacks and winding parries. If the broadsword was the master of the cut in British swordsmanship, Smallsword was absolutely the master of the thrust.

So why did swordsmen called the Smallsword the “Call of honour”? What is it? And how would you duel with it in 18th Century Britain?

Smallsword? Rapier? Foil? What’s the difference?

Swordsmen figured out pretty early on that sticking a metal point in someone works really well in a fight so historically we have a range of thrusting sword designs.

The Rapier

Let’s start with the ancestor of the smallsword, the rapier.

Just like the broadsword (link to own page) the rapier evolved from your typical knightly cross hilted sword. Sometimes a swordsman would curl a finger over one of the bars of the hilt for control, and unsurprisingly sometimes that finger took some damage. The solution?

Stick some more metal on your hilt. Specifically a ring over where the finger was curled over to protect it. Sometimes that finger ring wasn’t enough to guard it from cuts though. The solution?

Stick even more metal on your hilt. Bars kept being added and the hilt got more elaborate till eventually the complex “swept” hilted rapier of three musketeers fame appeared [1].

This roughly mirrors the evolution of the broadsword hilt but with a focus on the thrust not the cut. Swordsmen in history on both sides observed that the Brits had a habit of trying to hit things in a pinch whereas the Hispano-Italian men would try and stab things (perhaps explaining the split!).

The Smallsword

Now we get to the good stuff.

By the late 17thC no-one needed to carry a sword about as much and carrying a bulky lump of steel became an annoyance[2]. Not only that but fencing was changing.

Smaller circular parries and quick changes with the point were getting popular and they were much easier to perform with a lighter blade[1].

The thrusting sword had reached it’s logical conclusion as a shorter edgeless spike with a triangular cross-section, thin and stiff with a minimal handguard. Feather light in the hand, needle sharp at the tip, and well decorated to match the late 17thC invention of the suit [2]!

Because sure you want to win your duel, but you want to look good doing it.

The Foil

The foil was a blunt training tool for the smallsword [3] and some of the early foil fencing tournament rule-sets mirror the ones used today in Olympic fencing (like only counting thrusts to the torso).

The foil of the 18thC had a square cross-section blade making it cheaper to make, more flexible, and similar to the foil blades still used today.

This can be confusing as today’s épée blades (of Olympic fencing) have a triangular cross-section like the genuine smallsword. But the épée was a separate evolution of the French duelling sword (which evolved from the smallsword).

Simple! Sort of.

These days HEMA fencers can stick an épée blade on a classic smallsword hilt to simulate the real deal. If you’re looking to give it a try then allow me to plug our three week beginner swordsmanship course!

We’ll teach you the basics of 18thC swordsmanship through the medium of the Broadsword (after which you can move on to study to Smallsword, Broadsword and shield device, Quarterstaff, Bayonet and a host of other weapons).

With all those skills under your belt, you’ll be ready to defend the honour of yourself, your family, your family pet, whatever!

The 18th century duel

Meeting in the street with swords drawn ready to run each other through sounds like a pretty bloodthirsty way to pass the time, but the reality wasn’t always as bad as it sounds. We estimate over half the time both fighters lived to tell the tale[4]. Why?

It’s all in the prep work.

If you and I wanted to duel, we’d first need to…

Find “secondaries” (you and I being the “primaries”), friends who’ll keep things fair and break things up if it get too messy.

Find the nearest surgeon in case anyone needs patching up

Agree on rules, time and place!

Plenty of duels ended before they began with the primaries or the secondaries coming to an agreement.

Let’s say we both actually make it to the duelling grounds and we’re still game. After a few exchanges one of us gives the other some minor injury. If the reason for duelling wasn’t that bad (“hey you trod on my toe!”) then we shake hands and that’s the end of it.

If after a few wounds honour still isn’t satisfied then we carry on till one of us dies or cries uncle. They apologise at the point of a sword, get sewn up by the surgeon and maybe we end up good friends for life like these two:

“My grandfather then leaped off his horse, threw away his sword, and putting his broad dagger to the throat of Gilbert, told him to ask his life or die, as he must do either one or the other in half a minute.

Gilbert said he would ask his life only upon the terms that, without apology or conversation, they would shake hands heartily and be future friends and companions […] these terms being quite agreeable to my grandfather, as they breathed good sense, intrepidity, and a good heart, he aquiesced.

From that time they were the most intimately attached and joyous friends and companions of the county they resided in”[4]

All that makes duelling sound pretty romantic, even back in the 18thC the idea of the downtrodden classes fighting for honour and a justice the courts wouldn’t give them inspired more than a few folk heroes.

The reality is sometimes people cheated, back-stabbed and wore hidden armour. Here’s some advice from Donald McBane, an 18thC Scottish soldier, street brawler and occasional mugger [5]:

Never look away from your opponent or he’ll stab you in the back. Also don’t believe him if he says something to try and make you look away.

Never fall over, he’ll stab you in the back.

Never let him get behind you at any time before, during or after the duel. He’ll stab you in the back.

If he surrenders and you’re giving him his sword back, made sure you give it to him point first.

Never let him come close even if he’s acting friendly and he’s put down his sword or he’ll grab you.

Watch out for him throwing dust, his hat, or anything else in your face to blind you (he also notes if you can you should do the same to him).

If you lose a duel, your opponent might kick you when you’re down, take your sword and pawn it for booze

Beware running from a duel, you may take a smallsword thrust in the buttocks (I truly encourage you to read McBane’s memoirs at no point am I making this up)

Watch out for your opponent’s friends joining in or throwing stones at you while you duel him

From reading McBane’s memoirs we can deduce two things.

McBane was not a nice man (at least he was a practical one)

Duellists did not always play by the rules

How do you fight with a Smallsword?

With style.

There’s actually a lot of similarity between the techniques we see in our 18thC manuals vs moves we see used today in Olympic foil fencing, but there are some differences:

They advise never to thrust at the same time as your opponent to avoid a “Contre–temps ” where both fencers stab each other[6]

They advise not to attack further targets than the hand, forearm and arm. Getting too close risks a Contre–temps[7]

Grapples, disarms, palming the blade and trips are part of the style[8]

We see advice on how to deal with other weapons like the broadsword (link), Spanish rapier, smallsword and dagger pairings, all sorts[9]

The same basic techniques exist like lunging (big step to reach the other guy), “carte” and “tierce” parries (small motions of the hand and blade to parry left and right), and “circular” parries (small circular motions with the blade to gather up the opponents attack).

Simple feints are are there, parries and ripostes, binds, anyone familiar with modern fencing terminology could read a classic smallsword fencing manual and get a decent feel for it.

If you aren’t familiar…be prepared to brush up on your French. The British smallsword method borrowed a lot of terms from the French method (the Brits stealing things from the French being a popular historical pastime) and at least one master expresses his frustration over the habit:

“The name of this parade is Prime, and here is Second, Tierce, Quarte, Counter in Tierce, Counter in Quarte, Demicircle, and Octave. What a trumpery of frenchified names are here, which serves for nothing else that I know of but to stupify and embarrass people.”[3]

The main British influences on smallsword would probably be the way some masters tried to simplify the system by giving their opinions on the most important parries[7] or including as many dirty tricks as they could[5].

An older smallsword manual by Sir William Hope in 1707 even tries to simplify Smallsword to one major universal parrying position, including some cuts to save you from having to learn both broadsword and smallsword[6].

How you can get started

Learning British swordsmanship opens up a world of fun and fencing with new friends. It’s getting to experience history, satisfy your inner sword fan and get fit while doing it.

The best way to get started is by taking some lessons from an experienced coach and surrounding yourself with great people who’ve all been where you are. Starting from the very beginning.

Our three week beginner swordsmanship course takes you from total novice to being able to join in with group sparring and move on to other styles like Broadsword and shield devices, Smallsword, Quarterstaff, and more. You’ll learn the basics of attack and defence with the Broadsword including:

Footwork and posture

Three guards

Eight angles of attack

Three types of feints

Four ripostes

The four fundamentals of the British martial arts (Distance, Judgement, Time and Intention)

We’ll lend you a training sword and mask in class so you can get started safely. Students are allowed to spar after their first lesson but we recommend you complete the course before joining in with sparring.

The beginner course is priced at £30 per person for three weeks of training, and includes a free week of membership at the end so you can get a taste of our regular classes after you finish the course.

If after your first session of training you feel like HEMA isn’t for you, we’ll refund your money no questions asked.

The course is only run once every six weeks and places are limited, it’s best to email early to reserve your place and avoid disappointment.

Alfred Hutton. The Sword and the Centuries. London: Grant Richards; 1901.

Richard Cohen. By the Sword: A History of Gladiators, Musketeers, Samurai, Swashbucklers, and Olympic Champions. Random House Publishing Group; 2003.

John Godfrey. A Treatise Upon the Useful Science of Defense. London: T. Gardner; 1747.

Ben Miller. Irish Swordsmanship: Fencing and Duelling in Eighteenth Century Ireland. New York: Hudson Society Press; 2017.

Donald McBane. The Expert Swordsman’s Companion. Glasgow: J. Duncan; 1728.

William Hope. A New, Short and Easy Method of Fencing. Edinburgh: 1707.

John Ferdinand. The Sword’s-Man. Edinburgh: A. Robertson; 1788.

Zachary Wylde. The English Master of Defence. York: John White 1711.

Domenico Angelo. The School of Fencing. London: 1787