The Broadsword: Weapon of the Highlander, the Border Reiver, the Stage gladiator.

“It is impossible for any Man to Parry a Stroke or Cut, unless he truly understood Broad-Sword. What I’ve said, I think is sufficient to convince a rational Man in this Matter”- Zachary Wylde 1711 [1]

That’s a pretty big claim from 18th Century fencing master Wylde, right?

Well we’re going to look what a Broadsword is, who used it, how you fight with it, and see why is was so popular with swordsmen for hundreds of years.

What’s a Broadsword (and what is it broader than)?

The British Isles are no strangers to the idea of a straight bladed, two edged sword. Celts, Vikings and Crusaders would all be familiar with the concept of broad thin blade at your side as a secondary tool for defence (swords are great but usually play second fiddle to the spear and the bow).

But somewhere in the 16th century people evolved the design. Metal bars built around the cross-guard hilt to protect the hand began to develop into full steel baskets, even more protective than the swept hilts of the Italian rapiers.

We’re not sure who came up with this idea, but we have a few theories:

- The English borrowed the idea from the “Schiavona” basket hilted swords carried by eastern European mercenaries in Italy[2].

- Highland mercenaries touring Germany took the idea from there back to Scotland (and later imported German blades to fit Scot hilts[3]).

- It was an independent creation of the British Isles, but it’s hard to pinpoint from where. The earliest surviving examples were made in England but in the late century they called the hilts “Irishe” or “”Heland”[4].

Regardless the basket hilt completely changed sword-fighting on the Isles.

Imagine you’re a swordsman. You have two problems:

- You don’t want to get hurt (or killed!).

- You want the other swordsman (or swords-woman, Britain had plenty![5]) to stop trying to hit you. Usually solved by hitting them back till they stop.

To cut at the other guy you need to reach forward to swing your sword, but then you’ve exposed your hand. Before the basket everyone solved that with gauntlets, bucklers in the off hand to cover the sword hand or special footwork and weird looking guards to keep the hand back.

Now someone hands you a sword with a fancy steel basket around the hand.

Suddenly you get reach forward all you want, and no need to carry that heavy buckler or gauntlet! The forearm is still vulnerable and with new techniques come new problems but the part of you that wants to keep your fingers tells you it’s a good trade.

That is, unless you fancy the thrust over the cut. Then you might scoff at all these new basket hilted swords and go buy yourself the newest evolution of the rapier. A straight pointed blade with no edge, faster, lighter, slimmer.

What was everyone calling it again?

Oh yea, the Smallsword. It’s slimmer than the Broadsword. Which is broader than a Smallsword.

We weren’t a very creative people when it came to names.

Who wielded the Broadsword?

The 16th century

Swordsmen of the 16th century began to forge baskets straight onto their cruciform hilts, calling them “Short Swords” or “Single hilts[6]”, everyone knowing a good idea when they saw it.

George Silver’s “Brief Instructions” is the earliest manual we have for the British basket hilted sword[6]. It shows us a transitional mix of old and new swordsmanship, with wide sweeping movements to hack through helmets and armour. We also see some of the point forward guards that would eventually dominate British swordsmanship.

In Silver’s time duelling with rapiers was fashionable, he devotes a big chunk of his manual to criticising the Italian Rapier as a weapon badly made for defence.

Hilts too small, blades too long, with both rapier fighters usually ending up dying from their wounds.

Modern HEMA-ists who study Italian rapier manuals point out that Silver makes some straw-man arguments here and it really was the English people that started making themselves madly long rapiers that the Italian masters wouldn’t approve of [4].

Before the rapier craze the single hilted sword and buckler was in fashion. They said it was a very safe style, with roaming gangs of sword and buckler men brawling now and then just for fun:

“All the high streetes, were much annoyed and troubled with hourely frayes, of sword and buckler men, who tooke pleasure in that bragging fight; and although they made great shew of much furie, and fought often. Yet seldome any man hurt, for thrusting was not then in use: neither would one of twentie strike beneath the waste, by reason they helde it cowardly and beastly.”[4]

Because you might be a roaming thug with a sword, but you’re still a good sport.

The 17th century

By the 17th Century it was pretty unfashionable to be duelling. More rapiers around meant it was a deadlier pastime, and with some of the lower and middle classes getting in on the game[7] it just wasn’t as “classy” as before.

Duels might not have been as popular in England any more, but keeping a Broadsword with you (sometimes called a “Back-Sword”) was still a good idea.

Heading north?

Feuding Highland clans, Border Reivers and Wardens skirmishing over the Anglo-Scottish border[8]. With backsword and basket hilted daggers in hand they made travelling some roads dangerous.

Over in Ireland?

Highwaymen, gangs and coffee house duelling clubs. You might even be lucky enough to come across one of the famous Swordsmen-adventurers like William Lamport, soldier, pirate, and hero of the oppressed Mexican people (remembered as the inspiration for Diego de la Vega, aka Zorro![9]).

Surely you could travel about England safe and unarmed?

Maybe not. Our 17th century fighting manuals tell us what to do if you get attacked walking in the country[10], in the dark, in the pub[11], or when you’re sitting down minding your own business [12]!

The 18th century

This is where the Broadsword really makes a name for itself.

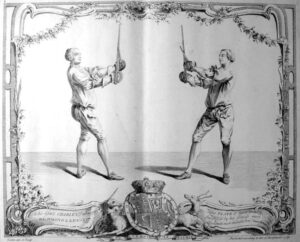

In the 18thC we have the Highlander’s charge with Broadsword and targe crashing into hedges of English bayonet points, fencing schools all across the Isles teaching Broadsword fencing to sword-scholars, and the best of them? Hungry for fame and fortune Stage Gladiators duke it out on stage for the people’s amusement.

Two combatants climb the stage to the sound of trumpets and drums[9], and watched by judges, ready surgeons and a cheering crowd they fight using any number of sharp weapons.

The most popular? Our friend the Broadsword.

Gladiators were amazingly skilled fencers with titles like “Tall boy”, “Invincible Irish Championess” and “The Terrible Champion”.

They say there’s no business like show-business, judge for yourself:

“Figg offered the serjeant the choice of swords, of several that were brought upon the stage, about two inches in breadth, and the points ground off. I had the curiosity to take one of them in my hand, and found that it was sharp edged enough to cut off an arm or a leg. […] The serjeant made a blow at Figg, which cut a pretty large piece of his stocking, without touching the leg. Figg, whose coolness and judgement were surprising, felt the stroke; ho, ho! Said he. I see thou hast a mind to my leg, but take care of thy own, and with the same breath whipped off a large piece of the calf of his adversary’s leg”[9]

Two of our 18thC fencing manuals were written by stage gladiators[13][14] and another two were written by masters taught by gladiators[15][16]. They had an impact on British fencing felt to this day.

The rest of our manuals were all written in this period by soldiers, fencing teachers and master swordsmen pressured into it by their friends! We take advice, techniques and practice methods from those manuals to study authentic historical sword fighting.

With so many manuals from all those expert swordsmen there’s plenty to work with to discover your own distinct style of Broadsword fencing.

How do you fight with a Broadsword (and targe, and buckler, and dagger)?

You book a spot on one of our beginner swordsmanship courses of course!

We’ll teach you every principle and technique hidden in those manuals to try against our other students.

But if you’re looking for hints before we see you in training…

How you fight with the single Broadsword

As much as it would be nice to be able to teach someone an entire martial art in a few paragraphs, we’ve not figured out how to do that yet. But we can take a look at how our man Zach Wylde who we quoted at the very start would begin to teach the principles of fencing…

- Posture. Similar to the typical Olympic fencing stance. Stand with your body edge on to your opponent, right foot forward (if right handed) toes pointed at him, left foot pointed out to your left to make a “T” shape with your feet. Then move them apart about shoulder width. Weight fully on the left leg! You might need to snatch the right leg away at a moments notice if it gets attacked.

- Place. What he means here is once you form your guard, don’t panic and jerk your arm away from where it needs to be. Broadsword fencing is all about movement efficiency and keeping your cool!

- Compass. You could describe this as keeping your sword arm (and your sword) between you and the other guy without over-swinging on the attack, and without making big movements when parrying.

- Step. Know how to lunge! The Olympic fencers know what I’m talking about. It’s a long step so you can hit the other guy from a good range.

- Time. Pick your moment. It’s can be a bad idea to attack at the same time as the other guy in case you end up both hitting each other. It’s a good idea to attack when he lets his guard slip to a bad position, or a moment before he finishes an attack if he’s striking with a bent arm. Tricky stuff!

- Distance. Always be the distance of a good lunge away from the other guy. Otherwise he’ll attack too fast for you to always react in time, or if he might try for a grapple before you realise.

- Patience. Angry fencers fence bad. Impatient fencers make mistakes. Patient fencers win by taking their…Time!

- Intention. Because patience doesn’t mean doing nothing. Scare your opponent by making it look like you’ll strike at one place, then go for another. Embrace the opportunities you’re given by his mistakes.

That’s oversimplified, but if you track down Zach Wylde’s 1711 fencing manual[1] you can read for yourself. Hopefully that gave you some insight into the mind of a single Broadsword fencer.

How you fight with Broadsword and buckler

The buckler was a small punch grip shield, usually round, sometimes with a spike attached[4]. It was particularly popular before the basket hilt because the buckler could guard your hand.

So how do you use it?

Learn to fight with the Broadsword. Then pick up a buckler.

Seriously it comes pretty naturally to a student once they learn the basics of single Broadsword.

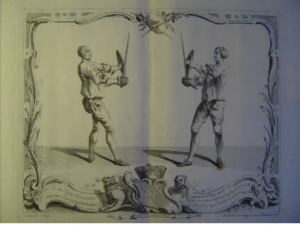

Here’s a picture straight out of a manual written by a Captain James Miller to give us an idea:

We do have two more hints from Donald McBane, soldier and occasional street brawler[14]:

- Keep your buckler straight out at arms length, just behind your sword to guard the forearm, or like Miller’s picture to guard one side as you guard the other with your sword.

- When you strike at your opponent’s legs guard your head with your buckler.

How you fight with Broadsword and targe

The targe was a wood and leather shield strapped to the forearm. Wider than a buckler, good for stopping pikes, bayonets, lead bullets, cuts and thrusts.

Along with the European “Rotella” Broadsword and targe fencing is one of the few examples of sword and shield fencing we get to study in HEMA.

It ended up being known as a Scottish speciality but there’s evidence showing the English[6] and the Irish[8] had been using “targets” (targes) for a while, Scotland just kept them around the longest.

Again, McBane figures anyone who can fence with a broadsword will get the hang of it easily. He gives some tips[14]:

- Most of his buckler advice still applies.

- Reach out and hold the shield with the forward edge pointed at your opponent, not with the flat face pointed towards him (otherwise you won’t be able to see around your targe).

How you fight with Broadsword and basket hilted dagger

Most European fencing styles explain how to use a dagger. British instructions on knife fighting usually boil down to:

- Be faster than the other guy[14]

- Don’t bother trying to “parry” a dagger [6][17]

- Don’t knife fight (way too dangerous. Are you nuts? [14])

Down to earth and practical advice. Much safer to protect yourself with a dagger and a proper sword.

Safer still? Put a basket on that dagger and make it about the length of your forearm. Later manuals don’t make much of a distinction between a dagger and a short Broadsword [18].

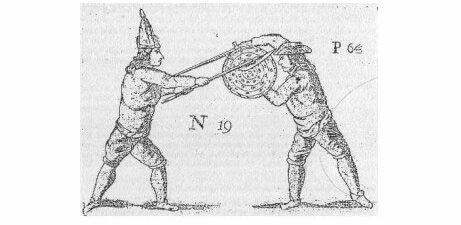

James Miller shows us an example[13]:

Most masters tell us to either block with the dagger and attack in the same moment with the sword [18] or block with both weapons then while you pin their sword with your dagger you strike back[6][11].

How you can get started

Learning British swordsmanship opens up a world of fun and fencing with new friends. It’s getting to experience history, satisfy your inner sword fan and get fit while doing it.

The best way to get started is by taking some lessons from an experienced coach and surrounding yourself with great people who’ve all been where you are. Starting from the very beginning.

Our three week beginner swordsmanship course takes you from total novice to being able to join in with group sparring and move on to other styles like Broadsword and shield devices, Smallsword, Quarterstaff, and more. You’ll learn the basics of attack and defence with the Broadsword including:

- Footwork and posture

- Three guards

- Eight angles of attack

- Three types of feints

- Four ripostes

- The four fundamentals of the British martial arts (Distance, Judgement, Time and Intention)

We’ll lend you a training sword and mask in class so you can get started safely. Students are allowed to spar after their first lesson but we recommend you complete the course before joining in with sparring.

The beginner course is priced at £30 per person for three weeks of training, and includes a free week of membership at the end so you can get a taste of our regular classes after you finish the course.

If after your first session of training you feel like HEMA isn’t for you, we’ll refund your money no questions asked.

The course is only run once every six weeks and places are limited, it’s best to email early to reserve your place and avoid disappointment.

Zachary Wylde. The English Master of Defence. York: John White 1711.

Christopher Thompson. Broadsword Academy. Lulu: 2011.

The National Trust for Scotland. Culloden: The swords and the Sorrows. Edinburgh: Self Published; 1996.

Paul Wagner. Master of Defence: The Works of George Silver. Colorado: Paladin Press; 2003.

Ben Miller. Irish Swordsmanship: Fencing and Duelling in Eighteenth Century Ireland. New York: Hudson Society Press; 2017.

George Silver. Brief Instructions upon Paradoxes of Defence. London; ca. 1605.

Francis Bacon. The Charge of Sir Francis Bacon Knight. London; 1614.

Keith Durham. The Border Reivers. London: Osprey; 1995.

Ben Miller. Irish Swordsmanship: Fencing and Duelling in Eighteenth Century Ireland. New York: Hudson Society Press; 2017.

William Cavendish. Mathematical Demonstrations of the Sorde. Newcastle: 1676.

Joseph Swetnam. The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence. London: Nicholas Oakes; 1617.

George Hale. The Private Schoole of Defence. London: 1614

James Miller. A Treatise on Backsword, Sword, Buckler, Sword and Dagger, Sword and Great Gauntlet, Falchon, Quarterstaff. London: 1735

Donald McBane. The Expert Swordsman’s Companion. Glasgow: J. Duncan; 1728.

John Godfrey. A Treatise Upon the Useful Science of Defense. London: T. Gardner; 1747.

Thomas Page. The Use of the Broad Sword.Norwich. M. Chase; 1746.

John Fairbairn. Unpublished knife fighting manuscript. 1955.

Archilbald MacGregor. MacGregor’s Lecture on the Art of Defence. Paisley: J. Neilson; 1791.