The Quarterstaff: Grandfather of all weapons

Whoever is master of the staff may defend himself against any one man, with back or small sword, as has often been experienced”- Donald McBane 1728

Chinese martial artists call the staff “the grandfather of all weapons”. When we study our historical fighting manuals the old British masters seem to absolutely agree when it comes to our own Quarterstaff.

But why? Who trained with it? And how do you use a Quarterstaff?

What’s a Quarterstaff?

A wooden staff 7-9 feet long would be called a “short staff”, a “long staff” being anything longer [1]. The best were made from Ash [2], and we have a few theories on the name:

One Victorian writer thought “Quarterstaff” referred to the way it was held[3]

A “quarter blow” used to mean a powerful swinging attack the staff could have been known for[4]

Making a Quarterstaff involves “Quartering” an ash tree into 4 parts. This is probably the simplest explanation.

Once you learned how to use the Quarterstaff you understood how to use all the pole-arms of the Isles [1][5]:

Spear

Javelin

Partisan

Glaive

Half pike

Bayonet

Battle axe

Halberd

English bill

Welsh hook

The last few had some extra tricks to learn but not bad for one little stick. Plenty of masters couldn’t praise it enough. Zach Wylde in 1711 writes “For a man that rightly understands it, may bid defiance and laugh at any other weapon”[6].

He goes on to say that Quarterstaff techniques are basically a fusion of Broadsword and Smallsword (the cutting and thrusting swords of the day). There’s an element of truth to that depending on the historical manual you’re studying.

Who trained with the Quarterstaff?

Anyone! Everyone!

From Thomas Barratt the stage gladiator called “old chopping block” teaching wandering woodsmen and gamekeepers“He taught the use of the broad sword for the army, and the quarter staff for park keepers, woodmen and others”[7]…

To Gentleman George Hale who recommended everyone study “single Rapier and Quarter-staffe “ to complete their martial arts education[8].

It was more commonly carried than the sword if we go by court records. In Nottinghamshire between 1485 and 1558 the staff was used in 53 out of 103 reported murders. The sword? Only 9[9].

Running a business? Better keep your staff handy. In the reign of Henry VIII inn owner Long Meg of Winchester had to challenge a dine and dash customer to “take that staffe and have a bout with me for thy breakfast”[9].

In the 15thC a Mr. Austin Bagger the Waterman was attacked by an angry rapier wielding passenger. Austin remembers his lessons and the customer gets “thoroughly beaten with oars”[9].

An essential skill for the small businessman it seems.

How do you use a quarterstaff?

We know what it looks like, we know how important it was, so how do you use it?

It depends who you ask.

The first instructions we get are from an anonymous 15thC manual in a manuscript “Cotton MS Titus A xxv”[10]. It’s…well let me give you an excerpt:

“And thanne iij quarteres And a rownde and ii rakes in þe rownes iij quarteres closed A j rounde war hym your armes be hynde han ij hawkes for þe wrong syde”

Yea. Attempts have been made to modernise the instructions but we’ll never know for sure how accurate the results are.

The next instructions we get are easier to follow. George Silver in the 16thC shows us some fundamentals[1]:

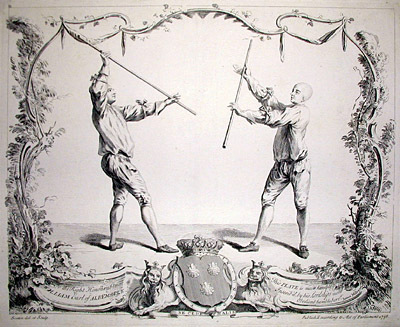

Guards that would be known as the point up “low ward” and the point down “high ward” (shown in the pictures below)

The thrust double (thrusting with both hands on the staff) and the thrust single (letting go with the forward hand for a longer ranged thrust)

Stronger than your opponent? Strike aside his staff then attack

Weaker than your opponent? When he swings at you pull back to avoid the attack then strike back (give em the “slip”)

Check those pictures again. That’s how you hold a quarterstaff! Don’t hold it in the middle, that’s called “Halfstaffing”. Hollywood lied to you.

Later on in the 17thC we find instructions from Joseph Swetnam[4], techniques influenced by rapier fighting. Old Joe Swetnam tells us the thrust is king when staff fighting and if your opponent lifts up his staff to strike…pop him in the face with a quick thrust single.

Can’t go too complex with a big ash stick.

His method of parrying involves moving the staff point around in a way that any rapier or smallsword fencer would recognise.

He also shows us a few thrusting feints (pretend to stab one bit, then stab another bit) and some striking feints (pretend to hit one bit, then hit another bit) even some hybrid feints (pretend to hit one bit, thrust at a lower bit).

The manual isn’t hard to read despite the dated language so if you can track down a copy it’s a good source of instruction.

Next we see Zach Wylde and his staff instructions[6]. He says by his time the Quarterstaff was losing popularity; “I wonder that it is not more in Vogue in this Nation, considering its Excellency” but he gives us two new techniques for the quarterstaff:

- Halfstaffing! He shows us how to hold the staff by the middle and rapidly strike with either end. This method was popular with the stage gladiators as seen in Captain James Miller’s drawings below. Lighter faster hits make for a better show.

- His guards are more broadsword-like, basically broadsword guards supported by the left hand. Instead of moving the tip of the staff to parry, now you move the base side to side.

Similar stuff show up in Donald McBane’s 1728[11] and Archibald McGregor’s 1791[5] manuals.

Moving into the 19th century. R.G. Allanson-Winn the Victorian self defence expert shows us parries moving from the base of the staff like Wylde[3], but his grip is closer to halfstaffing. He describes the thrust but calls it unsafe to practice.

Finally the last gasp of quarterstaff instruction, Thomas Mccarthy’s manual in 1883[12]. Allanson-Winn’s manual technically came out after Mccarthy’s but here we see the style finish it’s transformation.

No thrusts, all halfstaffing. By the 19th century it was more sport than self defence, kept alive by Victorian historical romanticism.

How you can get started

Learning British swordsmanship opens up a world of fun and fencing with new friends. It’s getting to experience history, satisfy your inner sword fan and get fit while doing it.

The best way to get started is by taking some lessons from an experienced coach and surrounding yourself with great people who’ve all been where you are. Starting from the very beginning.

Our three week beginner swordsmanship course takes you from total novice to being able to join in with group sparring and move on to other styles like Broadsword and shield devices, Smallsword, Quarterstaff, and more. You’ll learn the basics of attack and defence with the Broadsword including:

Footwork and posture

Three guards

Eight angles of attack

Three types of feints

Four ripostes

The four fundamentals of the British martial arts (Distance, Judgement, Time and Intention)

We’ll lend you a training sword and mask in class so you can get started safely. Students are allowed to spar after their first lesson but we recommend you complete the course before joining in with sparring.

The beginner course is priced at £30 per person for three weeks of training, and includes a free week of membership at the end so you can get a taste of our regular classes after you finish the course.

If after your first session of training you feel like HEMA isn’t for you, we’ll refund your money no questions asked.

The course is only run once every six weeks and places are limited, it’s best to email early to reserve your place and avoid disappointment.

George Silver. Brief Instructions upon Paradoxes of Defence. London; ca. 1605.

Donald McBane. The Expert Swordsman’s Companion. Glasgow: J. Duncan; 1728.

Allanson-Winn, Phillipps-Wolley. Broadsword and Singlestick with chapters on Quarterstaff, Bayonet, Shillalah, Walking-Stick, Umbrella and Other Weapons of Self Defence. London: George Bell & Sons; 1890.

Joseph Swetnam. The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence. London: Nicholas Oakes; 1617.

Archilbald MacGregor. MacGregor’s Lecture on the Art of Defence. Paisley: J. Neilson; 1791.

Zachary Wylde. The English Master of Defence. York: John White 1711.

Ben Miller. Irish Swordsmanship: Fencing and Duelling in Eighteenth Century Ireland. New York: Hudson Society Press; 2017.

George Hale. The Private Schoole of Defence. London: 1614

Paul Wagner. Master of Defence: The Works of George Silver. Colorado: Paladin Press; 2003.

Unknown. Cotton Titus MS. A. XXV, f.105. ca. 1475.

Donald McBane. The Expert Swordsman’s Companion. Glasgow: J. Duncan; 1728.

Thomas McCarthy. Quarterstaff. London: 1883.